Giving Up

Bailing out. Missing a lift. Saving your skinny little chicken neck.

In weightlifting, it is so necessary to correctly fail that dumping a barbell should be simultaneously taught with how to successfully make a lift. Also very necessary is to know when to cede to a workout or give up on a fatigued movement.

Which came first, the failure or the lift? The concept of "giving up" creates such a negative connotation that the motivational nonsense spread through life nowadays gives the impression that anyone willing to give up is a failure. Weak, inadequate, and/or inferior.

No better than a shivering chick... a wet newbie peeping for its mama hen.

Quite the contrary can be said when we look at making or failing a lift, whether it be a power lift like a Deadlift or a Squat, or an Olympic lift like a Jerk or a Snatch. It is those athletes that know how to bail out that keep themselves safe, healthy, and strong.

Those athletes that have trained the correct bar path in order to efficiently make a successful lift know this. When something goes wrong, when a movement is incorrect, even in the slightest, failure means you live to lift another day.

Plus, heavy squats are always the go-to fix for chicken legs. So the skill of dumping a barbell helps to correctly use the progressive overload principle.

For those who haven’t failed, their potential in whatever endeavor they seek in life has not been fully realized. They haven’t tested the upper limits of their capabilities. In weightlifting it's knowing how to safely fail that shows strength through intelligence.

Like a smart, egghead brainiac, strength can come in many forms.

Similar to weightlifting, if a gymnastics movement or other bodyweight exercise starts to lose efficacy, if the body is shutting down to a point of inefficiency, then giving up is a necessary evil. Sure, there are times to drive ahead, to push through fatigue and complete a workout as it was written. The mental gains are particularly worthwhile in this regard, so long as the movements are still safely executed. But the moment where one puts themselves at high risk for injury, at risk for overtraining or under-recovery, this is the time when a workout becomes completely negotiable. At this point, the decision to end a session early is not weak in any regard; it is not incompetent or pitiful. Instead, it is mentally strong. It is egotistically impressive, actually. Realizing that range of motion is breeched and safety is compromised is in fact a very, very strong attribute.

Know when to fold 'em. When it's time to "snuff the rooster." This is tricky, for sure, but highly necessary in strength and conditioning.

Dan Maggio has done such a great job at succinctly highlighting the specifics of intentional bailing from a lift that it deserves reprinting here to his credit on how to implement this into your training.

How to Miss a LiftWhen teaching/coaching weightlifting related lifts, the FEET MUST ALWAYS MOVE in order to get the base of support out from under the falling bar. [Source: The Importance of Missing Lifts and Bailing Out]

- Bailing out of the Back Squat: Release grip on bar, push chest and head UP to pop the bar off your back, JUMP feet forward to avoid the bar hitting your heals if you land on your knees.

- Bailing out of Front Squat: Release grip on bar, drop the elbows as you simultaneously JUMP your feet back and push your hands to the ground. Not jumping your feet back can cause the dumped bar to crash on your thighs and knees. (This bail is the same as bailing out of a Clean.)

- Missing the Snatch (in front): Actively EXTEND arms forward. JUMP your feet backwards.

- Missing the Snatch (behind): Actively EXTEND arms backward (as if giving “Jazz Hands”). JUMP FORWARD quickly to avoid the bar landing on shoulders or back. It is vital to extend the arms backward fully to create more space and avoid collision.

- Missing the Jerk: If the barbell is already moving forward, JUMP the body back while pushing the bar away. Similarly, if stability is not maintained and the barbell drifts backward, JUMP forward away from the weight.

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall... As far as "giving up" goes, we're on the topic of succumbing to a lift or movement in a positive, thoughtful way. Not just being lazy or unmotivated.

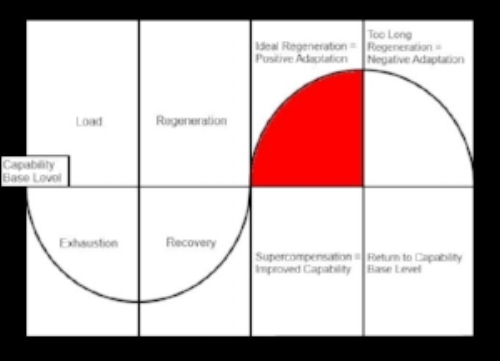

In reference to being smart with a conditioning workout or to avoid overtraining/under-recovering, some specifics have been highlighted in past articles. Check "MetCons" and "Progress" to get the full explanation.

Our basic concept is always to pursue lifelong fitness. If we're looking to stay healthy for years to come, then one day does not make or break a workout regimen. However, one day can turn into a week, then a month, and so on. So therefore, since a longer term view on fitness best serves our ever-aging bodies, then pushing to a point of immense fatigue is a slippery slope. Particularly dangerous is exercise addiction.

All the king's horses and all the king's men can't put an addict's fitness together again.

One must ask some important questions: "Am I working hard because this will gain me the necessary muscle breakdown and/or cardiovascular stress?" vs. "Am I doing this because I'm stubborn and masochist and want to prove something to myself?" Be honest.

In other words, be cautious of forcing a conditioning workout if you crash and burn. Once you bonk, die... lay an egg.

Finish what you started if you can, sure, but only if is still safe in the realm of total work. For example, is the run mileage just too high? Burpee reps too many? Barbell weight too heavy? Plus, will you be sore and out of commission for the rest of the week? Time to be smart and give in.

A full week of quality work is more beneficial than one day of feigned glory.

As I've stated before, if a lifting session or post-workout skill work aren’t going well, then a new PR or your first muscle-up probably won’t happen on your 20th, 30th, or 100th attempt. Being persistent is one thing, being stupid is another. Stop. Cut your losses. Look ahead to the next day.

This is a plan of action where giving up is actually moving forward.

So off you go with brains and brawn. Never be chicken to check yourself before you wreck yourself.

- Scott, 6.22.2015